Family history is all about finding and reading documents, whether you look at scanned images at our site or hunt for the originals in record offices. As you work your way back from recent certificates to older wills and parish registers, the writing on these documents can be tricky, as the words and their meanings—and even the shapes of the letters themselves—have changed over time. Understanding these ancient scrawls can often be the key to comprehending your ancestors’ lives.

Common problems

Generally, older records are harder to read. Documents from the 19th and 20th centuries mainly use the words and writing styles we’re used to today, so they don’t present too many problems. Where you do run into difficulties, it’s often because of bad handwriting or poor equipment—blobs of ink obscuring letters and writing that’s so faded it’s almost illegible, for example.

As you move into the 17th and 18th centuries, you’ll find far more variation. Spelling can be particularly difficult, as spellings weren’t standardized until compulsory education began around 1870. Surnames and place names in particular can have a wide variety of spellings, even on the same page.

Documents from around this time will also start to introduce you to different styles of handwriting. Although these are all in English, they can look quite different from modern script.

Different styles

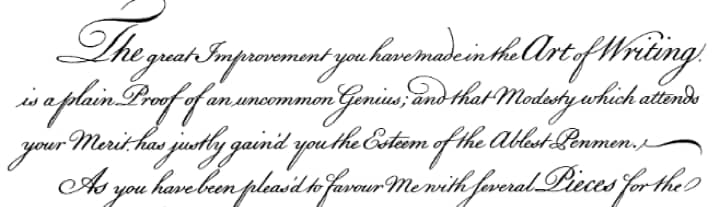

The first style you’ll come across will probably be Round Hand. This free-flowing, expressive way of writing is especially common in personal papers and letters from the 18th century. It’s not too far away from how we write today, although early examples may use different shapes for capital letters, almost interchangeable i’s and j’s, and a long s.

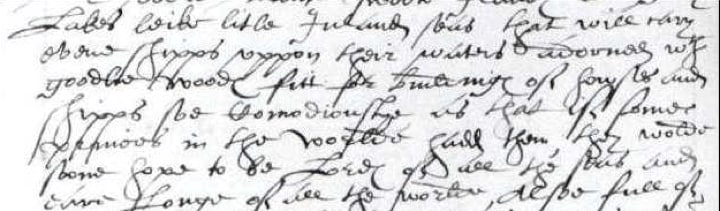

These variations are a hangover from the precursor to round hand, secretary hand. This style emerged in the 16th century and dominated in England for almost 200 years, so you’ll often come across it on parish registers. Secretary hand can look like nothing but scribbles at first, but take the time to look at individual letters in turn and you’ll often find you can decipher it.

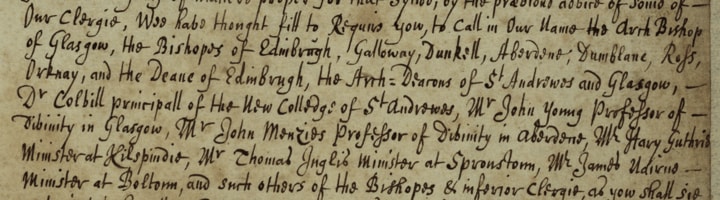

A 17th-century alternative was italic hand. This style developed in Italy though the Renaissance. It’s far easier to read than secretary hand, but unfortunately, it’s less common.

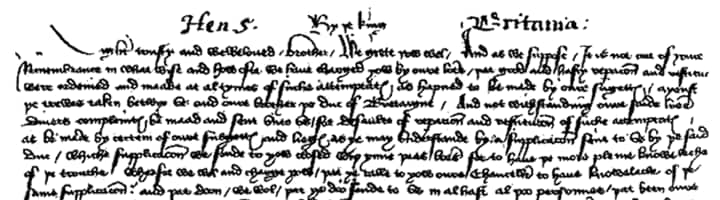

Before this time, most of the population couldn’t write at all, so there was little need for a universal style. Several royal and government departments developed their own scripts. The most successful of these was Chancery hand, used at the Royal Chancery in Westminster. You may come across it in legal documents, especially wills. It’s usually very neat, but the formal letter shapes can be confusing.

Tips

Printing or enlarging the image

If you’re working with an original document, scan it; that way, you can handle it without damaging it and zoom in on parts of the document.

Tricky letters, spellings, and abbreviations

There were no standard spelling rules before 1755 in England or before 1828 in the United States.

- In the past, a long form of the letter s looked like our contemporary letter f.

- Words currently spelled with the letter i were often formerly spelled with the letter y; for example, “mine” was spelled “myne.”

- The letters u and v were frequently interchanged; the word “ever,” for example, was often spelled “euer.”

- The letter j was often replaced with i, so the name “James” may appear as “Iames.”

- The word cousin often meant niece or nephew.

- The title Mrs. could show high social status, not necessarily marital status.

- Good brother or good sister in a document means brother- or sister-in-law.

- The term in-law was also used to describe step-parents.

- The word infant was used to describe both a baby and a person under legal age.

Abbreviations and contractions were often used to save space on paper, which was an expensive commodity.

Here are some common shorthand references:

- The letter y often replaced the letters th; for example, “the” was often written “ye.”

- The symbol @ sometimes replaced the word per, for example if you come across @week it most likely means “per week.”

- The symbol &, which replaces and, often had personal variations and could change from author to author.

- Superscripts were used more often in old English. You see them used most often today as ordinal indicators, such as 1st, 2nd, 3rd etc. Some examples in old English include wch , wth for “which” and “with,” and maty for majesty.

Strategies

- Look up unfamiliar or archaic words and abbreviations online.

- Research the kind of document you’re working with; certain documents may have specific phrases, jargon, and abbreviations. Understanding the document’s historical context can help you read the handwriting and understand its meaning.

- Read the document aloud; hearing it may help you to recognize unfamiliar words.

- Write the words yourself by placing tracing paper over a photocopy of your document and tracing each word. Creating the characters of the text may help you understand the words and the context.

- Make an alphabet chart as you go. Write out the alphabet on a separate piece of paper, then copy examples from the document for each letter, both lower- and uppercase. It’s usually easiest to identify letters in more obvious words like names and places, then refer to your chart to help with more difficult words.